Yosemite National Park is the birthplace of American environmental activism, as well as modern rock climbing, backpacking, and landscape photography. So much that we consider as American “wilderness” started right here. Ian Ramsey gives some insight into some of this Yosemite history and how it lives on today in this incredible place.

From my backcountry overlook on the Snow Creek trail, I’m looking across the valley at Half Dome. To my left, Cloud’s Rest rises into the sky. The dimensions are unfathomable-Is that distant ridge two miles or twenty miles away? I haven’t seen anyone in hours.

Over the past few days, I’ve run, power-hiked, skidded and sprinted my way around the valley. I’ve also sat in quiet wonder, watching the light reflect off of El Cap, listening to waterfalls, and watching deer ambling through meadows.

In between backcountry adventures, I’ve also gotten glimpses of industrial tourism-trails, restaurants, and visitors centers packed full of families, senior citizens, crying toddlers, international tourists, and scout troops. Overfull parking lots and long lines at ice cream stands. With 4.5 million visitors in 2019, Yosemite is the fifth-most visited National Park. Movies like Free Solo have featured the park, and if you open any Patagonia catalog or climbing or backpacking magazine, you’re sure to see images of the great granite walls, alpine meadows and forested slopes. Heck, Yosemite was even in a Star Trek movie.

The History of Yosemite

Native Lands of the Ahwahnechee

The name “Yosemite”-which means “killer” in Miwok-was the name that the local nineteenth-century settlers mistakenly called the local Ahwahnechee tribe who lived in the valley. The Ahwahnechee, relatives of the Northern Paiute and Mono tribes, had lived in the valley that they called “Ahwahnee”-meaning “big mouth”-for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. Indeed, the valley has been inhabited for over 3000 years. In 1849, their lives were disrupted when the California gold rush brought 90,000 non-native settlers and miners to the region.

In 1851, as part of the Mariposa Wars intended to suppress Native American resistance, the State of California funded a private militia, and these soldiers -the first documented Europeans to enter the valley in Yosemite history-drove most of the Ahwahnechee people from the area. While a few native people held on, living and working in the valley, they still faced terrible discrimination.

A century later, in 1969, the National Park Service would continue this inequity, evicting the remaining Native people from their residences and destroyed their village as part of a fire-fighting exercise. Today, the Park Service is doing its best to honor the legacy Native people’s connection to this land, but there is much work to be done.

Early Development

Starting in 1855, entrepreneur James Mason Hutchings started to publicize Yosemite and bring tourists to the valley, where he built roads and a hotel. Other hotels and businesses started to pop up in the valley, and tour operators started to cut roads through sequoia trees. As awareness of the area’s unique beauty spread, along with fears of rampant development, prominent citizens advocated for protection of the valley. In 1864, the US Congress passed a bill creating the Yosemite Grant-it was the first instance of park land being set aside specifically for preservation and public use. This set the precedent for the creation of Yellowstone as the first National Park a few years later, in 1872.

Muir and early conservation

In 1878, a Scottish immigrant named John Muir arrived in San Francisco and immediately set off on foot across the central valley for Yosemite. He would spend the next eight years living in, and exploring the valley. During that time he would build a small cabin, work as a sheepherder and run a sawmill, but mostly he would explore and adventure around Yosemite and the Sierras.

Muir’s writings about Yosemite and the Sierras would not only introduce the region to the world, but would also introduce new ideas about conservation, earth-based spirituality, mountain-climbing, ecology, and glaciology to the world. Muir hosted people like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Teddy Roosevelt, who shared his message. In 1890, after decades of activism by Muir and others, Congress signed an act to create Yosemite National Park. Two years later, in 1892, Muir would create the Sierra Club to inspire people to hike the Sierras and protect them.

In 1923, despite decades of efforts of Muir and others, the nearby Hetch Hetchy Valley was dammed to provide water for the growing Bay Area, a conservation loss in Yosemite history that would serve as a cautionary tale for decades.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, a young photographer and Sierra Club member named Ansel Adams made the valley and Sierras even more famous with his evocative black and white photos of the landscape. Through the work of Adams and the Sierra Club, the John Muir Trail was created, as well as nearby Kings Canyon National Park. Adams, who would go on to become America’s most famous landscape photographer, became synonymous with conservation, documenting, and advocating for, the National Parks.

As automobile travel, the highway system, and the population of California increased, visitation to the park increased. In the 1920s, the park concessionaire, hoping to make Yosemite “The Switzerland of America” even put in a bid to host the winter Olympics in the park, but fortunately it was unsuccessful.

As I look out across the valley, I’m so grateful that this wasn’t developed for the Olympics. Where I ran yesterday across granite ledges, there might have been a ski lift. Tolumne Meadow, with its carpets of richly-scented wildflowers, might have been yet another hotel.

I’m so grateful that running here in Yosemite still translates into a wild, sensory experience of cold rushing water and the pitchy scent of sequoias. I’m glad that I can feel the warmth of the granite on my face and that, an hour later in a completely different ecosystem, my eyes are ringing bright with the colors of subalpine paintbrush and monkeyflowers. And I’m glad that, because Yosemite wasn’t developed as much for industrial tourism, it was discovered by rock climbers.

Scaling the granite monoliths

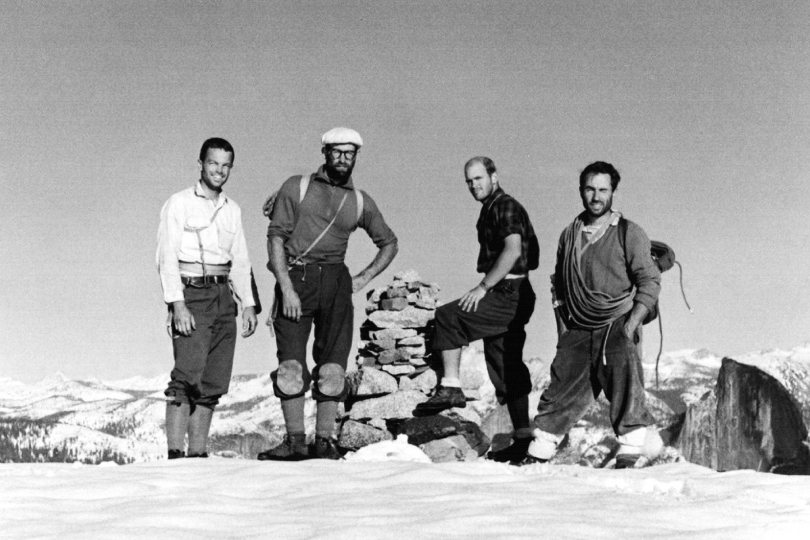

In the 1950s and 60s, Yosemite became the center of American rock climbing, with climbers like Yvon Chouinard (who would go on to found the company Patagonia) and Royal Robbins putting up many first routes and making big walls like El Cap and Half Dome world-famous. They would also develop new climbing technologies like molybdenum pitons and nuts. Their achievements would inspire generations of climbers like Jim Bridwell, Lynn Hill, and Ron Kauk to live at the infamous Camp Four and push the limits of human possibility.

Today groundbreaking climbers like Emily Harrington, Alex Honnold, and Tommy Caldwell are still sending routes that would have been impossible even a few years ago. One of the early Yosemite climbers-David Brower-would go on grow the Sierra Club from a regional hiking and advocacy group to America’s most prominent environmental organization.

Yosemite and the Sierras are also the birthplace of American backpacking, where people inspired by Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder’s “Rucksack Revolution” started putting on Kelty framepacks in the 1960s. Today, nearly 4,000 people hike the John Muir Trail each year, half of them through-hiking the entire Pacific Crest Trail.

Running amongst the monoliths

While Yosemite is best-known for climbing, there is a rich modern history of trail-running here, particularly on the John Muir Trail. Over the past decade, an assortment of ultrarunners have kept lowering the FKT (fastest known time) for the 212 mile trail, including Hal Koerner, Mike Wolfe, Darcy Piceu, and Leor Pantilat, before Frenchman Francois D’Haene set the current record at 2 days, 19 hours, and 26 minutes. Former FKT holder Catra Corbett actually yo-yo’ed the trail, running the 424(!) miles in just over 12 days. Elsewhere in the park, climber Dean Potter set the FKT for Half Dome just two weeks before dying in a tragic wingsuit accident in 2015. Recently, Jason Hardrath set a number of records on the Yosemite Valley Loop El Capitan, and the Trans-Yosemite Trail. Countless other trails offer opportunities for runners to explore, whether they set records or not.

Yosemite, 2021

Today, Yosemite is a perfect example of the challenges the National Park Service faces as it tries to balance tourism and recreation with conservation. A century of Forest Service fire suppression policies combined with drier, hotter weather and smaller annual snowpack due to climate change have created a landscape that is prone to intense annual wildfire. These fires disrupt visitation and destroy ecosystems and infrastructure.

At the same time, record-setting numbers of tourists and their cars mean that that the valley’s air quality can sometimes be substandard. Backpackers, hikers and big-wall climbers often find themselves in situations where rescue and other medical services are called for. The park service struggles to create a safe, quality experience for all visitors while maintaining the unique landscape and ecology of Yosemite.

And today, as I watch clouds drift across the tip of Half Dome, I’m one of those grateful visitors. If you rock climb, or backpack, or enjoy photography, or consider yourself an environmentalist, or enjoy public lands-anywhere in the world- you owe a debt of gratitude to this place. But all of those stories and facts and historical figures fade away when you look at the 2,425 foot high Yosemite Falls, or find yourself in a Sequoia grove. Yosemite’s greatest legacy is awe, the opportunity to deeply experience something bigger, wilder and more beautiful than you knew was possible.

Run Yosemite with Aspire!

If Yosemite with less crowds and more mountain running sounds like your kind of daydream, you are only one step away from a dream come true. Join us for some truly elevated trail miles on top of the Sierras.

We’ve already sold out 2 trips for 2021. The third trip has a handful of spots left. Hop on board!

Ian Ramsey

With three decades spent exploring the PNW and Alaska, Ian is based in Maine, where he directs the Kauffmann Program for Environmental Writing and Wilderness Exploration, and teaches writing, ecology, brain science, music and mindfulness to high school students. With over two decades leading trips and expeditions across the US, Alaska and internationally, he loves empowering people to take agency in their lives and discover new places. Ian is a poet and graduate of the Rainier Writing Workshop, and his writing has been featured in places like Terrain.org, Orion and High Desert Journal. He also directs a community steelband, loves kayaking big water, drinks copious amounts of coffee, geeks out around nutrition, literature and fitness, and was once a member of an Inuit Dance Troupe.

Check out his website at Ianramsey.net