During Native American Heritage month, we invite you to take a deeper look with us at the connection between the first people of the Pacific Northwest and the earth. Learn about the impact of the modern day stewardship of indigenous tribes on our rapidly changing environment through the eyes and experience of Stillaguamish Tribe Marine Biologist Francesca Perez.

“I don’t believe in magic. I believe in the sun and the stars, the water, the tides, the floods, the owls, the hawks flying, the river running, the wind talking. They are measurements. They tell us how healthy things are. How healthy we are. Because we and they are the same…”

-Billy Frank Jr.

When you think of salmon do you envision rivers thick with red fishy backs? Sockeye leaping into the maw of a grizzly bear? Consider old growth cedars, containing ocean-nutrients delivered by eagles dining on spawned out fish. Freshwater mussels hidden in stream gravels, dependent on juvenile salmon for their offspring’s survival.

Consider also the autumn rain run-off swelling creeks with invisible chemicals that kill female coho ripe with eggs.

There are tangles in the Pacific Northwest web of life.

The Salmon People

The salmon we know today evolved millions of years ago. The best adapted species survived the Pleistocene, successfully responding to landscape changes created by the ice ages. They spawn in our rivers and streams, nesting in glacial debris. They hatch and swim downstream to our ocean, where they eat and grow fishable. Those that escape nets and predators return to their birth stream years later, navigating by unseen forces.

The indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest adapted to post-glacial conditions along with salmon, and they thrived in these food-rich, coastal environments. Their complex societies are marked by ceremony, story, art, and trade. Hundreds of thousands of Indians celebrated and served their Salmon Family well for millennia, until European fur traders arrived in the early 19th century.

Settlement

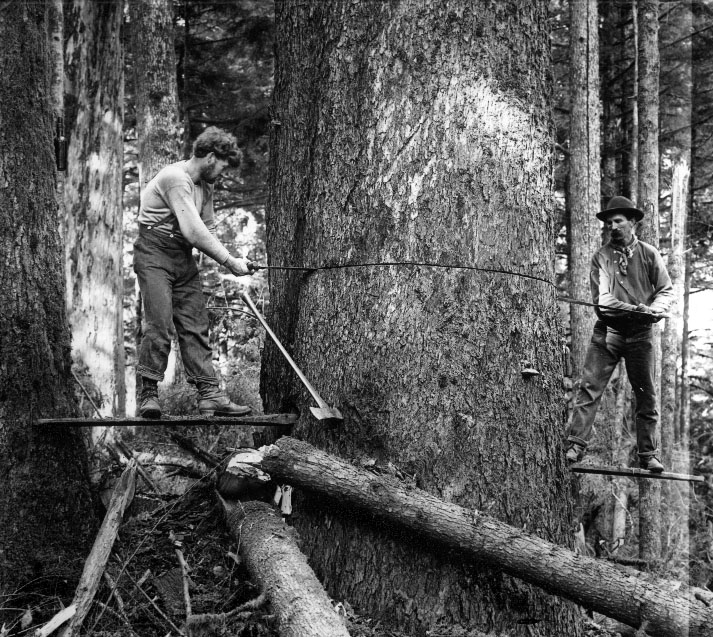

The settlement and resource extraction that followed so completely transformed the landscape that by the 1880s hatcheries were needed to sustain the drain. It addition to vast over-harvest, a gauntlet of obstacles were created that impacted salmon survival.

Removing beavers and their complex infrastructure, diking rivers, and draining estuaries all depleted juvenile salmon habitat by removing wetlands and small channels that support first year development.

Old growth timber harvest, transported by rail along those armored banks, robbed rivers of the wood that creates cool, deep pools for refuge in summer.

Dams blocked off hundreds of miles streams for spawning. And thanks to modern society, regional marine waters have become so laden with chemicals that salmon who grow to adulthood in Puget Sound are a cancer risk to human and orca alike.

Fish managers have reduced harvest by 80-90%, yet salmon populations continue to decline. What can be done?

Stewardship

In the words of UBC Chancellor Steven Point, “We are only borrowing and using the world.”

Health of salmon relates directly to the spiritual and physical well-being of local indigenous people. For this reason, each Tribe in the Puget Sound region dedicates a large percentage of revenue to restore habitat and rebuild salmon stocks. As co-managers ( Boldt Decision 1974 ), Treaty Tribes operate natural resource departments similar to those of the State, but with the luxury of focusing on specific river basins. Tribal governments can streamline priority projects, and are leaders in research, monitoring, and restoration.

Since Chinook were listed as Threatened by the Endangered Species Act in 1999, Puget Sound tribes have worked with State and Federal leaders to channel fiscal resources to help salmon recovery. They co-write management plans, develop land-protection strategies, and review grants for restoration projects. Limited tribal staff often juggle a variety of tasks ranging from sampling plankton to commenting on development permits to walking the rivers each September recording data on spawned out fish (everyone’s favorite).

Restoration work can involve volunteers to replant floodplain forests in winter, or tribal youth to test water quality in summer. Large scale projects restore miles of stream habitat through culvert repair and

small (plus sometimes large) dam removals. Community engagement with stakeholders leads to dike removal, freeing rivers and estuaries to flow and channelize naturally. And millions of salmon fry, that would not otherwise survive, are released from hatcheries every year.

This is but a small sample of indigenous stewardship activities in Puget Sound that provide hundreds of jobs and is leveraged with similar efforts by government agencies. Yet with population growth and climate change, we continue to lose more habitat than can be restored. The work requires continued persistence and creative, inclusive thinking.

Read: The State of Our Watersheds

Stewardship means caring for someone else’s property or space. Indigenous leaders recognize we must care for the land as their ancestors did, not for the next year or next generation, but for the seven generations still to come, and the Salmon People are leading the way.

Keeping the marine environment clean and healthy is a lifelong pursuit that Franchesca is fortunate enough to work toward daily in her job as a biologist for the Stillaguamish Tribe.

She oversees the Marine Stewardship and Shellfish Program, managing multiple monitoring and research projects, advocating for the Tribe in emerging marine resource issues, and by seeking shellfish harvest opportunities for Tribal members.

Franchesca holds an MS in Marine and Estuarine Science from Western Washington University. Outside of work, Franchesca enjoys exploring wild places and taking her kids to the beach as often as they’ll let her.