Fire lookouts in the North Cascades inspired a wave of beat generation poets whose withdrawal from societal expectations and literary musings inspired the birth of North American mountain culture. The influence of these poet-climbers has impacted generations of wilderness aficionados and reverberates in the hearts and minds of mountain people the word over.

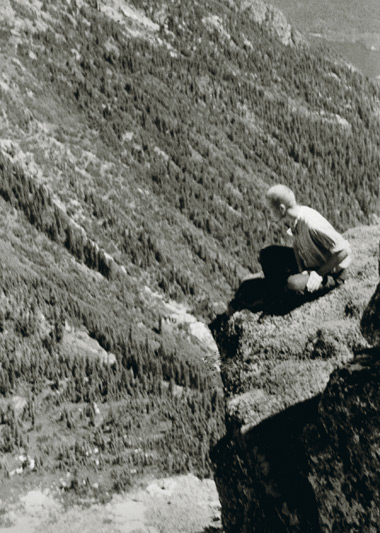

In February of 1952, a twenty-one year old graduate of Reed College applied for a seasonal job with the US Forest Service as a North Cascades fire lookout, requesting the “highest, most remote, and most difficult-of access lookout” possible. He received an assignment as the summer lookout on Crater Mountain, a severe 8000 foot peak in the North Cascades of Washington.

Due to excessive snow, he wasn’t able to get to the summit lookout cabin until late July, and even then equipment had to be winched up the steep cliffs to the small wood-and-glass hut. The new fire lookout woke on his first morning to five inches of fresh snow and inverted icicles on the guy wires.

Little did he know that his time as a lookout over the next two summers would be transformative not only for him, but for American culture, inspiring two of his Beat Generation friends to undertake similar journeys, and pointing countless Americans in directions that would include meditation, backpacking, mountain culture and sports, and environmental activism. His name was Gary Snyder.

Gary Snyder grew up in the Pacific Northwest during the Great Depression, in a working-class family with socialist union politics. As a kid seeing Chinese landscape paintings in the Seattle Art Museum, Snyder was struck by the similarities between the mountains of China and those of his native Cascades. Moreover, with lots of Japanese immigrant neighbors, he was intrigued by Asian culture, particularly Buddhism.

As a teen, Snyder had started climbing mountains under the tutelage of the Mazamas mountaineering club, summiting Rainier, Hood and St Helens. At the intersection of these interests, he developed a deep and enduring interest in Zen Buddhism and its spiritual mountain traditions. During his time at Reed College, Snyder worked summers on trail crew, fire fighting and logging, and grew accustomed to rugged outdoor work and living. By early 1952 he was living in San Francisco, studying Asian languages at UC Berkeley and practicing Zen Buddhism. He knew that he wanted to explore Buddhist practice in the mountains, so he applied to be a lookout.

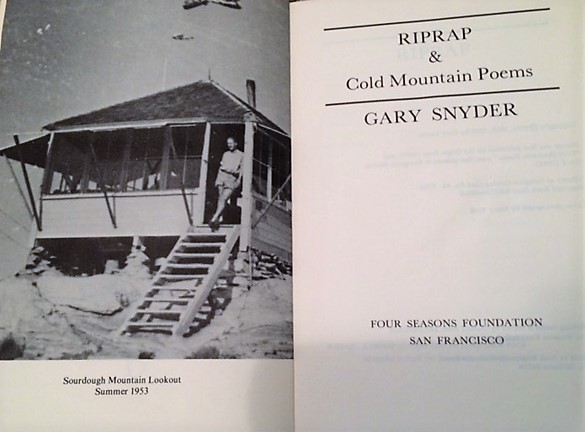

Snyder spent his six weeks on top of Crater Mountain in a rhythm of fire watching, hiking and scholarship. Every day he would scan the surrounding ridges, using a device called an Osborne Fire Finder, to estimate precise locations of fires, and communicate via radio with the Ranger Headquarters. Beyond that, aside from daily tasks like splitting wood and melting snow for water, he was free to brew green tea, read Buddhist texts like the Diamond Sutra, meditate, practice calligraphy, and think deeply, inspired by the endless mountains around him. The following summer he would work as a fire lookout on another peak, Sourdough Mountain. There he continued to study the Dharma and write poems influenced by ancient Asian poets. A perfect example is “Mid-August on Sourdough Mountain”:

Down valley a smoke haze

Three days heat, after five days rain

Pitch glows on the fir-cones

Across rocks and meadows

Swarms of new flies.

I cannot remember things I once read

A few friends, but they are in cities.

Drinking cold snow-water from a tin cup

Looking down for miles

Through high still air.”

Snyder would inspire two other writers to become fire lookouts: his Reed college roommate Phillip Whalen and Beat Generation icon Jack Kerouac. Whalen spent three seasons as a fire lookout and the time inspired many great poems and a lifelong dedication to Zen practice.

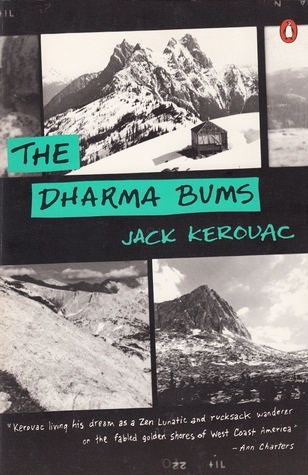

In the spring of 1954, Kerouac, still an unknown writer, moved to San Francisco, where he met and spent a great deal of time with Snyder, eventually writing the novel The Dharma Bums about their time together. These two, along with a broader band of misfit writers in San Francisco including Snyder, Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Michael McClure, came to be known as the Beat Generation. This pivotal group sparked the beginning of the American counterculture that would eventually become the hippie movement.

Kerouac went on to spend a season as a fire lookout on Desolation Peak, the most remote lookout in the North Cascades. For Kerouac, who struggled his entire life with addiction and depression, it was the most peaceful time of his adult life. After his lookout season, he would return to civilization, and within a year become a celebrity after the publication of On The Road. In the ensuing years he would struggle with fame, never recapturing his mountain joy, and pass away in 1969 of alcohol-related issues.

Snyder went on to live in Japan for a decade, studying Zen, before returning to California and homesteading in the Sierra Nevada foothills, where he still lives today. He is last living member of the Beat Generation. He would go on to be at the forefront of the hippie movement, along with Ginsberg and Timothy Leary, and also to win the Pulitzer Prize for his poetry, which combined Asian Buddhist perspectives with the kind of ecological consciousness he had developed as a fire lookout.

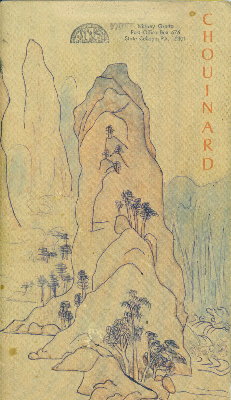

The influence of Snyder and his lookout compatriots can be seen in myriad places, including the birth of modern American rock climbing and adventure culture (Yvon Chouinard’s first Chouinard Equipment Catalog features Chinese landscape paintings). The “Rucksack Revolution” that Snyder and Kerouac foretold was manifested as a 1970s explosion of interest in backpacking and hiking that has continued to today. Snyder, Whalen and Kerouac all studied and practiced the kind of meditation that science and culture is increasingly recognizing as important for happiness and cognitive performance. Indeed, Phillip Whalen went on to the become a full lineage-holder Zen Roshi after decades of study and practice. They also laid the groundwork for a generation of PNW poets and translators of ancient Buddhist texts like Red Pine and Sam Hamill. As Snyder wrote about lineage in his poem “Axe Handles,”:

…Pound was an axe,

Chen was an axe,

I am an axe

And my son a handle, soon

To be shaping again, model

And tool, craft of culture, we go on.

Ian Ramsey is a writer, educator and ultrarunner. He directs the Kauffmann Program for Environmental Writing and Wilderness Exploration. You can find out more about him at www.Ianramsey.net.

North Cascades fire lookouts are features of these Aspire trips:

Desolation Duo

Territory Run Camp

Stehekin

North Cascades Traverse