Most runners who’ve been at it for a while will unfortunately feel that tell-tale twinge somewhere in their bodies that eventually turns into a full-blown injury. I’ve been there; a lot.

Whether it’s an ankle sprain or a knee strain, Achilles tendonitis or a stress fracture, it’s no secret that injuries are devastating to runners, regardless of what level you run at. The internet is awash in information- some of it really good, some of it really not so good, about what to do when injured. An important (and often overlooked) topic to consider is what happened along the way that gets us runners to the point of being vulnerable to developing injuries3. Patterns of persistent weakness, compensation, and a “no pain no gain” mentality often land athletes in the doctor’s office when it’s already too late3,5,13. Here we’ll take a look at some injuries that are ubiquitous in the running world, and some things to watch out for leading up to these issues.

It goes without saying that runners of all flavours get injured. All the time. Every distance from the 100m dash to the 100 miler incurs its own special set of injury risks, and trail runners are no exception. Sure, the softer surfaces of single track and scree are always better than pounding the pavement. But just because we trail enthusiasts often go to extreme lengths to avoid the track or the asphalt doesn’t mean we’re immune to all the same pitfalls other runners face. Sometimes it can feel like maddeningly brief periods of blissful trail cruising between one injury recovering and another rearing up.

My mother has been a constant training partner over the years (on her 60-year-old single speed Schwinn – no joke) and a voice of supremely logical reasoning. She has always astutely commented on why a myopic, mono-sport devotion rarely leads to athletic longevity. She is right. Runners need time off, they need to cross train, they need to do all the non-running things that will ensure they can keep running for decades into the future.

But it’s hard. There is nothing I would love better than to run 365 days a year, decade after decade. From the time I was a competitive gymnast in primary school all the way up to the current day, my mom has rightly interrogated my compulsion for excessive loyalty to a single sport. All this from a lady who is not a runner nor a trained coach but has a beyond normal capacity for level-headed decision making, an invaluable outsider perspective, and doesn’t suffer from a running addiction. What I’m getting at here is that sometimes the most honest reflection of what’s in your own best interest comes in the form of a wakeup call from an injury, or from a highly perceptive parent, coach, or spouse.

There are an infinite number of ailments trail runners might be hit with, but here we’ll go over a couple of the most common ones and some of the likely musculoskeletal imbalances and weaknesses that lead up to said injuries. You’ll notice a lot of crossover and commonality in symptoms and likely weakness patterns in the injuries listed below. I should stress here before jumping into the following overviews that whilst a lot of runners do encounter injury, just because you have a post-run twinge does not automatically equate to catastrophic or even moderate injury. Try to be critically self-evaluative. Channel that inner ‘mom calm.’ Ask yourself how long you’ve experienced symptoms, if you’ve had any incident or event that escalated your problem, and if it has been unresponsive to cursory rest and time off. If you feel your issue isn’t improving with rest, icing (if appropriate), cross training, and other self-care then give a thought to whether or not you’re headed for injury. It’s a delicate balance between not manifesting something that isn’t there and equally not living in ignorant bliss about what might be brewing.

[Quick Note: The following provides general information to those reading but is in no way intended to diagnose any ailment, prescribe treatment, or predict rehabilitation outcomes. Please always talk with your Primary Care Physician, PT, or other healthcare provider for clinical assessment and treatment].

Plantar Fasciitis

- What is it?

This is a condition of persistent irritation and subsequent inflammation of the fascia on the underside of the foot3,4,7,8. The plantar fascia is a multilayer of fascial tissue that has anchor points throughout the toes, tarsals, and foot arch and attaches to the Achilles tendon at the calcaneus (heel) bone15. From the Achilles, fascial connections can be traced further into much of the posterior lower leg compartment and plantarflexor musculature15.

Fascia used to be treated as a throwaway tissue by many surgeons, but in recent decades significant research has shown fascia is highly innervated15, important for internal structural support and more complex than we first thought. This is great to know, because understanding that a tissue can alter the bony structure around it or convey pain signals to the brain when it’s injured is key to solving problems with it. When a runner has plantar fasciitis it’s often characterized by early morning onset of pain and stiffness in the arch, pain at the heel, and the inability to put your full weight onto the affected foot (which requires the plantar fascia to stretch under your bodyweight)7,8,12.

- What can cause it?

Running on hard surfaces too often, increasing mileage too rapidly, lack of mobility (flexibility) of the foot arch, tight Achilles and calf muscles, poor foot mechanics, improperly fitted shoes and/or orthotics3,4,12.

- What’s usually weak?

Tibialis anterior (shin muscle), ankle stabilizers, gluteal muscles7.

- What’s usually too tight?

The plantar fascia itself, surrounding foot fascia, Achilles tendon, Flexor Hallucis Longus (big toe flexor), Soleus, Gastrocnemius8.

- What to do?

The best place to begin is to start being diligent about gaining back mobility in your foot and calf soft tissues (active or instrument assisted stretching is great for structures like the plantar fascia)8. This could be foam rolling your calves, using an ice cup on your inflamed plantar fascia post-run, getting manual therapy done to release the calf muscles, and taking some time off. Back off your training volume and tone down the climbing for a bit12,13. Ascending puts incredible extra stress on the plantar fascia, Achilles, and calf, and if your fascia is already inflamed too much climbing before you’ve achieved full recovery could aggravate it further. A good secondary stop along the rehabilitation journey is strengthening the areas you’ve identified as being weak and regaining stability within the pelvis and lower extremity as a whole4,7.

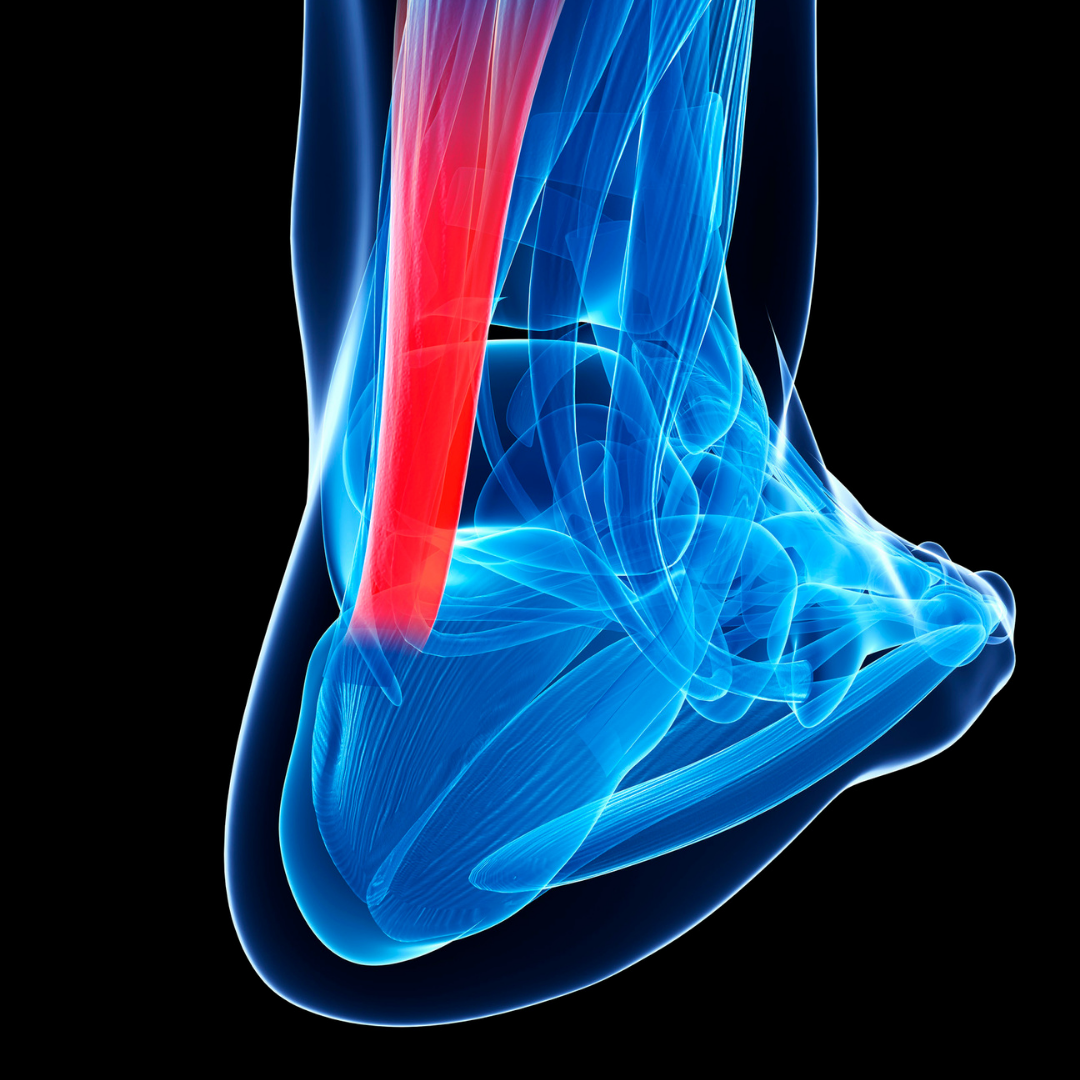

Achilles Tendinosis and Tendonitis (Fun fact: they’re not the same thing!)

- What is it?

Achilles Tendinosis is characterized by repeated damage to the Achilles tendon, connective fascia, and paratendon2,3. Tendinosis can cause rigidity of the tendon, pain that’s unresponsive to standard home-treatment, thickening of the tendon itself, or all of the above2. Tendonitis, on the other hand, is typically a result of shorter-term aggravation and has all the hallmarks of a typical inflammatory condition (that’s what the ‘-itis’ suffix stands for). Your Achilles may feel warm and painful to the touch and show edema (swelling) as well. It is important to distinguish between these two conditions because the treatment protocols vary for each1,2,3. Some of the information you may need to definitively know what’s going on with your Achilles can only be accomplished through medical imaging (like a diagnostic Ultrasound or MRI)16.

- What can cause it?

Tendinosis is typically due to prolonged, repeated microtearing in the tendon which causes long term degeneration of the tendon. The body lays down a haphazard matrix of scar tissue over these tears, and this scarring appears to create pain in the tendon2. There are a lot of theories out there as to why tendinosis develops and persists in some more than others. Foot mechanics, genetics, tendon composition, previous injury—the list is long1,2.

Tendonitis can arise post-injury, after increasing training volume too fast, or moving into shoes that are not suited to your foot mechanics2,3.

- What to do?

The recovery protocol for tendinosis is unfortunately considered to be a much longer slog than that of many other musculoskeletal injuries1. The Achilles is a unique tendon for a lot of reasons: in anatomical design, physiological function, and biological composition2. The amount of force it withstands during running is absolutely incredible (many multiples of your body weight)15. So as you might imagine, it takes a fair amount of work to rehab the Achilles. [I should mention here that this sort of complex rehab should definitely be done under the direction of Sports Physician or Physical Therapist].

Achilles tendinoses generally do not respond to the standard RICE (rest, ice, compress, elevate) treatment because the condition is not inflammatory strictly speaking, it’s degenerative2,9. Rehabilitation instead involves eliminating the aggravating activity that is causing repeated injury (sadly this usually means running) for weeks up to months depending upon the severity. You’ll also probably be tasked with making alterations that take some of the stress off the Achilles, like adding a heel lift to your shoe and saying goodbye to those zero drop running shoes you were so excited about. The next step usually is to slowly regain strength in the calf and tendon itself so progressively higher loads can be tolerated without pain16. When you do return to running it will probably be slow and infuriatingly intermittent, or you’ll land right back where you started. Connective tissues in the body need time to adapt to the compressive forces of running after time off, and if you start running at full steam too quickly your connective tissues might not handle the abrupt stress increase well1,3,16.

Achilles tendonitis, while still not a condition to be sniffed at, generally requires shorter treatment time and recovery than tendinosis2. This is an injury that does usually respond well to RICE9. Depending on where you fall on the spectrum of debate with taking NSAIDs, taking an anti-inflammatory to mitigate pain will be up to you and should be cleared with your doctor. (Most clinicians will likely advise you to take some form of NSAID if you hobble into their office with a clear case of tendonitis). With time off from running think about non-weight bearing cross training, strength training, and mobility exercises. With that said, runners can still be side-lined for many weeks with tendonitis or recurring tendonitis if they jump back into training prematurely.

Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS)

- What is it?

This is yet another connective tissue issue, specifically with the thick band of fascia called the Iliotibial Band (ITB). The ITB runs from the outside of your hip down to the outside of your knee15,18. Most people experience pain with ITBS at the outside of the knee, but the area of inflammation often stretches beyond the localized point of symptomatic pain6. The ITB can rub on the bony prominences of both the femur (thigh bone) and some of the other structures that comprise the knee, and this friction is what causes pretty intense lateral knee pain for a lot of people dealing with ITBS.

- What causes it?

ITBS is usually caused by overuse (ie: too much training volume), lack of stabilizing hip strength, poor running form causing misalignment of the ITB, or due to prolonged periods of sitting12.

- What’s usually weak?

Glute Med, Glute Max, lumbar stabilizers such as Quadratus Lumborum, and Multifidus, core musculature such as Transverse Abdominus, and the Obliques5,6,17.

- What’s usually too tight?

Hip flexor muscles: TFL, Rectus Femoris, Iliopsoas, maybe the ITB itself depending upon your individual postural alignment17.

- What to do?

You guessed it, lay off the running and employ the RICE recovery protocols. Consider going to a manual therapist to regain mobility all along the ITB and connective tissues surrounding it. If you feel your home-care regimen isn’t helping, then it’s time to head to the PT5,13,17,18.

While this is absolutely only a short list of some common runner issues, the main takeaway here is that injuries are often the symptomatic and painful result of wider ranging weakness and misalignment. It’s important to do some detective work to determine what landed you in the position of being injured in the first place. If something is correctable (and a heck of a lot of issues are) then do you best to find the root of the problem. Treating only the most painful and symptomatic areas might work in the short term, but it won’t address any deeper issues you’ve got going on. At the risk of sounding like a broken record- the best way to prevent these injuries worsening when they arise is to take your recovery seriously, don’t cut corners, and don’t cheat yourself into thinking somehow you possess superhuman physiology that allows you half the healing time of normal humans. It really is too bad we aren’t all equipped with Wonder Woman’s ability to spring back up after a minor (or lethal) injury. Ah, the trials of being a mere human.

References:

- Alfredson, H., & Cook, J. “A treatment algorithm for managing Achilles tendinopathy: new treatment options.” British journal of sports medicine. 2007. 41 (4): 211-216.

- Bass, E. “Tendinopathy: why the difference between tendinitis and tendinosis matters.” International journal of therapeutic massage & bodywork. 2012. 5 (1): 14.

- Bertelsen, M.L., Hulme, A., Petersen, J., et al. “A framework for the etiology of running‐related injuries.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2017. 27 (11): 1170‐ 1180.

- Dos Santos, B., Corrêa, L. A., Santos, L. T., Meziat Filho, N. A., Lemos, T., & Nogueira, L. A. C. “Combination of hip strengthening and manipulative therapy for the treatment of plantar fasciitis: a case report.” Journal of chiropractic medicine. 2016. 15(4): 310-313.

- Fredericson M, Cookingham CL, Chaudhari AM, et al. “Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome.” Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 2000. 10(3): 169–75.

- Fredericson, M., Wolf, C. “Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners.” Sports Med. 2005. 35: 451–459.

- Lee, J. H., Park, J. H., & Jang, W. Y. “The effects of hip strengthening exercises in a patient with plantar fasciitis: A case report.” Medicine. 2019. 98(26).

- Looney, Brian, et al. “Graston Instrument Soft Tissue Mobilization and Home Stretching for the Management of Plantar Heel Pain: A Case Series.” Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2011. 34 (2):138-42.

- Lopez, R. G. L., & Jung, H. G. “Achilles tendinosis: treatment options.” Clinics in orthopedic surgery. 2015. 7(1): 1-7.

- Magnussen, R. A., Dunn, W. R., & Thomson, A. B. “Nonoperative treatment of midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2009. 19 (1): 54-64.

- Medeiros, Diulian Muniz, and Tamara Fenner Martini. “Chronic Effect of Different Types of Stretching on Ankle Dorsiflexion Range of Motion: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Foot. 2018. 34: 28-35.

- Petraglia, F., Ramazzina, I., & Costantino, C. “Plantar fasciitis in athletes: diagnostic and treatment strategies. A systematic review.” Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2017. 7(1), 107.

- Pope, Rodney Peter, et al. “A randomized trial of preexercise stretching for prevention of lower-limb injury.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2000. 32 (2): 271-277.

- Rowlett, Carrie A., et al. “Efficacy of Instrument-Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization in Comparison to Gastrocnemius-Soleus Stretching for Dorsiflexion Range of Motion: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2019. 23 (2):233-40. Web.

- Schünke, M., E. Schulte, and U. Schumacher. Thieme Atlas of Anatomy. Edited by L. Ross, and E. Lamperti. Thieme Medical, Stuttgart, 2006.

- Shalabi, A., Kristoffersen-Wiberg, M., Aspelin, P., & Movin, T. “Immediate Achilles tendon response after strength training evaluated by MRI.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004. 36 (11): 1841-1846.

- Strauss, E.J. (MD), Kim, S. (MD), Calcei, J.G., Park, D. (PT, DPT) “Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Evaluation and Management” American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon. 2011. 19 (12): 728-736.

- Terry GC, Hughston JC, Norwood LA. “The anatomy of the iliopatellar band and iliotibial tract.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1986. 14 (1): 39–45.